Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma Treatment

General Information About Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma

Key Points

- Childhood soft tissue sarcoma is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in soft tissues of the body.

- Soft tissue sarcoma occurs in children and adults.

- Having certain diseases and inherited disorders can increase the risk of childhood soft tissue sarcoma.

- The most common sign of childhood soft tissue sarcoma is a painless lump or swelling in soft tissues of the body.

- Diagnostic tests are used to diagnose childhood soft tissue sarcoma.

- If tests show there may be a soft tissue sarcoma, a biopsy is done.

- There are many different types of soft tissue sarcomas.

- Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

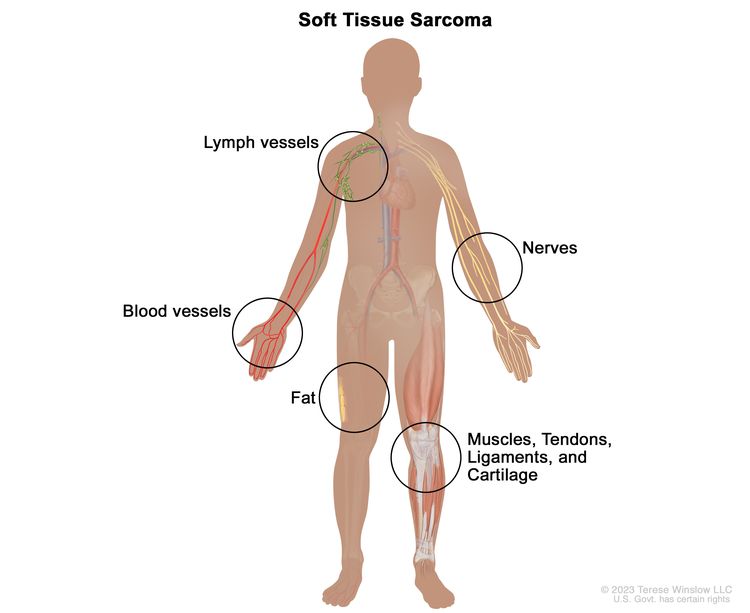

Childhood soft tissue sarcoma is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in soft tissues of the body.

Soft tissues of the body connect, support, and surround other body parts and organs. The soft tissue include the following:

- Fat.

- A mix of bone and cartilage.

- Fibrous tissue.

- Muscles.

- Nerves.

- Tendons (bands of tissue that connect muscles to bones).

- Synovial tissues (tissues around joints).

- Blood vessels.

- Lymph vessels.

Soft tissue sarcoma may be found anywhere in the body. In children, the tumors form most often in the arms, legs, chest, or abdomen.

Soft tissue sarcoma occurs in children and adults.

Soft tissue sarcoma in children may respond differently to treatment, and may have a better prognosis than soft tissue sarcoma in adults. (See the PDQ summary on Soft Tissue Sarcoma for information on treatment in adults.)

Having certain diseases and inherited disorders can increase the risk of childhood soft tissue sarcoma.

Anything that increases your risk of getting a disease is called a risk factor. Having a risk factor does not mean that you will get cancer; not having risk factors doesn’t mean that you will not get cancer. Talk with your child’s doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

Risk factors for childhood soft tissue sarcoma include having the following inherited disorders:

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

- RB1 gene changes.

- SMARCB1 (INI1) gene changes.

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

- Werner syndrome.

- Tuberous sclerosis.

- Adenosine deaminase-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency.

Other risk factors include the following:

- Past treatment with radiation therapy.

- Having AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) and Epstein-Barr virus infection at the same time.

The most common sign of childhood soft tissue sarcoma is a painless lump or swelling in soft tissues of the body.

A sarcoma may appear as a painless lump under the skin, often on an arm, a leg, the chest, or the abdomen. There may be no other signs or symptoms at first. As the sarcoma gets bigger and presses on nearby organs, nerves, muscles, or blood vessels, it may cause signs or symptoms, such as pain or weakness.

Other conditions may cause the same signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of these problems.

Diagnostic tests are used to diagnose childhood soft tissue sarcoma.

The following tests and procedures may be used:

- Physical exam and health history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- X-rays: An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body onto film, making pictures of areas inside the body.

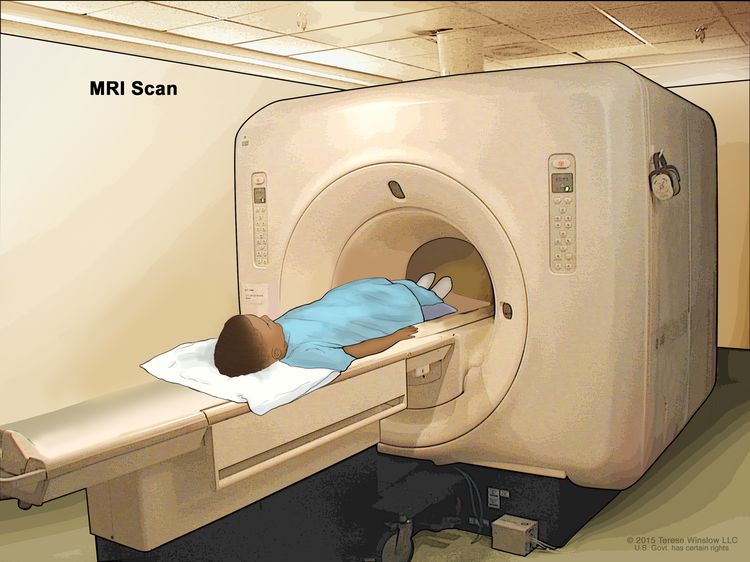

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas of the body, such as the chest, abdomen, arms, or legs. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

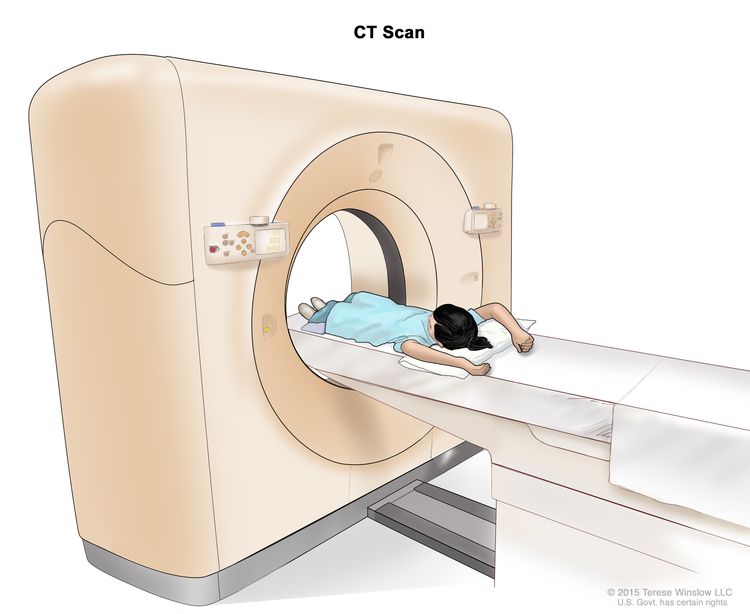

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen. The child lies on a table that slides into the MRI scanner, which takes pictures of the inside of the body. The pad on the child’s abdomen helps make the pictures clearer. CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the chest or abdomen, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen. The child lies on a table that slides through the CT scanner, which takes x-ray pictures of the inside of the abdomen. - Ultrasound exam: A procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. The picture can be printed to be looked at later.

If tests show there may be a soft tissue sarcoma, a biopsy is done.

The type of biopsy depends, in part, on the size of the mass and whether it is close to the surface of the skin or deeper in the tissue. One of the following types of biopsies is usually used:

- Core needle biopsy: The removal of tissue using a wide needle. Multiple tissue samples are taken. This procedure may be guided using ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI.

- Incisional biopsy: The removal of part of a lump or a sample of tissue.

Excisional biopsy: The removal of an entire lump or area of tissue that doesn’t look normal. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells. An excisional biopsy may be used to completely remove smaller tumors that are near the surface of the skin. This type of biopsy is rarely used because cancer cells may remain after the biopsy. If cancer cells remain, the cancer may come back or it may spread to other parts of the body.

An MRI of the tumor is done before the excisional biopsy. This is done to show where the original tumor formed and may be used to guide future surgery or radiation therapy.

If possible, the surgeon who will remove any tumor that is found should be involved in planning the biopsy. The placement of needles or incisions for the biopsy can affect whether the whole tumor can be removed during later surgery.

To plan the best treatment, the sample of tissue removed during the biopsy must be large enough to find out the type of soft tissue sarcoma and do other laboratory tests. Tissue samples will be taken from the primary tumor, lymph nodes, and other areas that may have cancer cells. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells and to find out the type and grade of the tumor. The grade of a tumor depends on how abnormal the cancer cells look under a microscope and how quickly the cells are dividing. High-grade and mid-grade tumors usually grow and spread more quickly than low-grade tumors.

Because soft tissue sarcoma can be hard to diagnose, the tissue sample should be checked by a pathologist who has experience in diagnosing soft tissue sarcoma.

One or more of the following laboratory tests may be done to study the tissue samples:

- Molecular test: A laboratory test to check for certain genes, proteins, or other molecules in a sample of tissue, blood, or other body fluid. A molecular test may be done with other procedures, such as biopsies, to help diagnose some types of cancer. Molecular tests check for certain gene or chromosome changes that occur in some soft tissue sarcomas.

- Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) test: A laboratory test in which the amount of a genetic substance called mRNA made by a specific gene is measured. An enzyme called reverse transcriptase is used to convert a specific piece of RNA into a matching piece of DNA, which can be amplified (made in large numbers) by another enzyme called DNA polymerase. The amplified DNA copies help tell whether a specific mRNA is being made by a gene. RT–PCR can be used to check the activation of certain genes that may indicate the presence of cancer cells. This test may be used to look for certain changes in a gene or chromosome, which may help diagnose cancer.

- Cytogenetic analysis: A laboratory test in which the chromosomes of cells in a sample of tumor tissue are counted and checked for any changes, such as broken, missing, rearranged, or extra chromosomes. Changes in certain chromosomes may be a sign of cancer. Cytogenetic analysis is used to help diagnose cancer, plan treatment, or find out how well treatment is working. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a type of cytogenetic analysis.

- Immunocytochemistry: A laboratory test that uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient’s cells. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to the antigen in the sample of the patient’s cells, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test may be used to tell the difference between different types of soft tissue sarcoma.

- Light and electron microscopy: A laboratory test in which cells in a sample of tissue are viewed under regular and high-powered microscopes to look for certain changes in the cells.

There are many different types of soft tissue sarcomas.

The cells of each type of sarcoma look different under a microscope. The soft tissue tumors are grouped based on the type of soft tissue cell where they first formed.

This summary is about the following types of soft tissue sarcoma:

Fat tissue tumors

Liposarcoma. This is a cancer of the fat cells. Liposarcoma usually forms in the fat layer just under the skin. In children and adolescents, liposarcoma is often low grade (likely to grow and spread slowly). There are several different types of liposarcoma, including:

- Myxoid liposarcoma. This is usually a low-grade cancer that responds well to treatment.

- Pleomorphic liposarcoma. This is usually a high-grade cancer that is less likely to respond well to treatment.

Bone and cartilage tumors

Bone and cartilage tumors are a mix of bone cells and cartilage cells. Bone and cartilage tumors include the following types:

- Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. This type of bone and cartilage tumor often affects young adults and occurs in the head and neck. It is usually high grade (likely to grow quickly) and may spread to other parts of the body. It may also come back many years after treatment.

- Extraskeletal osteosarcoma. This type of bone and cartilage tumor is very rare in children and adolescents. It is likely to come back after treatment and may spread to the lungs.

Fibrous (connective) tissue tumors

Fibrous (connective) tissue tumors include the following types:

Desmoid-type fibromatosis (also called desmoid tumor or aggressive fibromatosis). This fibrous tissue tumor is low grade (likely to grow slowly). It may come back in nearby tissues but usually does not spread to distant parts of the body. Sometimes desmoid-type fibromatosis can stop growing for a long time. Rarely, the tumor may disappear without treatment.

Desmoid tumors sometimes occur in children with changes in the APC gene. Changes in this gene may also cause familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). FAP is an inherited condition (passed on from parents to offspring) in which many polyps (growths on mucous membranes) form on the inside walls of the colon and rectum. Genetic counseling (a discussion with a trained professional about inherited diseases and options for gene testing) may be needed.

- Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. This is a tumor of the deep layers of the skin that most often forms in the trunk, arms, or legs. The cells of this tumor have a certain genetic change called a translocation (part of the COL1A1 gene switches places with part of the PDGFRB gene). To diagnose dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, the tumor cells are checked for this genetic change. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually does not spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body.

- Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. This cancer is made up of muscle cells, connective tissue cells, and certain immune cells. It occurs in children and adolescents. It most often forms in the soft tissue, lungs, spleen, and breast. It frequently comes back after treatment but rarely spreads to distant parts of the body. A certain genetic change has been found in about half of these tumors.

There are two types of fibrosarcoma in children and adolescents:

- Infantile fibrosarcoma (also called congenital fibrosarcoma). This type of fibrosarcoma usually occurs in children aged 1 year and younger and may be seen in a prenatal ultrasound exam. This tumor is fast growing and is often large at diagnosis. It rarely spreads to distant parts of the body. The cells of this tumor usually have a certain genetic change called a translocation (part of one chromosome switches places with part of another chromosome). To diagnose infantile fibrosarcoma, the tumor cells are checked for this genetic change. A similar tumor has been seen in older children, but it does not have the translocation that is often seen in younger children.

- Adult fibrosarcoma. This is the same type of fibrosarcoma found in adults. The cells of this tumor do not have the genetic change found in infantile fibrosarcoma. (See the PDQ summary on Adult Soft Tissue Sarcoma Treatment for more information.)

- Myxofibrosarcoma. This is a rare fibrous tissue tumor that occurs less often in children than in adults.

- Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. This is a slow-growing tumor that forms deep in the arms or legs and mostly affects young and middle-aged adults. The tumor may come back many years after treatment and spread to the lungs and the lining of the chest wall. Lifelong follow-up is needed.

- Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma. This is a rare fibrous tissue tumor that grows quickly. It can come back and spread to other parts of the body years after treatment. Long-term follow-up is needed.

Skeletal muscle tumors

Skeletal muscle is attached to bones and helps the body move.

- Rhabdomyosarcoma. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common childhood soft tissue sarcoma in children 14 years and younger. (See the PDQ summary on Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment for more information.)

Smooth muscle tumors

Smooth muscle lines the inside of blood vessels and hollow internal organs such as the stomach, intestines, bladder, and uterus.

- Leiomyosarcoma. This smooth muscle tumor has been linked with Epstein-Barr virus in children who also have HIV or AIDS. Leiomyosarcoma may also form as a second cancer in survivors of inherited retinoblastoma, sometimes many years after the initial treatment for retinoblastoma.

So-called fibrohistiocytic tumors

- Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor. This is a rare tumor that usually affects children and young adults. The tumor usually starts as a painless growth on or just under the skin on the arm, hand, or wrist. It may rarely spread to nearby lymph nodes or to the lungs.

Nerve sheath tumors

The nerve sheath is made up of protective layers of myelin that cover nerve cells that are not part of the brain or spinal cord. Nerve sheath tumors include the following types:

- Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Some children who have a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor have a rare genetic condition called neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). This tumor may be low grade or high grade.

- Malignant triton tumor. These are very fast-growing tumors that occur most often in children with NF1.

- Ectomesenchymoma. This is a fast-growing tumor that occurs mainly in children. Ectomesenchymomas may form in the eye socket, abdomen, arms, or legs.

Pericytic (Perivascular) Tumors

Pericytic tumors form in cells that wrap around blood vessels. Pericytic tumors include the following types:

- Myopericytoma. Infantile hemangiopericytoma is a type of myopericytoma. Children younger than 1 year at the time of diagnosis may have a better prognosis. In patients older than 1 year, infantile hemangiopericytoma is more likely to spread to other parts of the body, including the lymph nodes and lungs.

- Infantile myofibromatosis. Infantile myofibromatosis is another type of myopericytoma. It is a fibrous tumor that often forms in the first 2 years of life. There may be one nodule under the skin, usually in the head and neck area (myofibroma), or several nodules in skin, muscle, or bone (myofibromatosis). In patients with infantile myofibromatosis, cancer may also spread to organs. These tumors may go away without treatment.

Tumors of unknown cell origin

Tumors of unknown cell origin (the type of cell the tumor first formed in is not known) include the following types:

- Synovial sarcoma. Synovial sarcoma is a common type of soft tissue sarcoma in children and adolescents. It usually forms in the tissues around the joints in the arms or legs, but may also form in the trunk, head, or neck. The cells of this tumor usually have a certain genetic change called a translocation (part of one chromosome switches places with part of another chromosome). Larger tumors have a greater risk of spreading to other parts of the body, including the lungs. Children younger than 10 years whose tumor is 5 centimeters or smaller and has formed in the arms or legs have a better prognosis.

- Epithelioid sarcoma. This is a rare sarcoma that usually starts deep in soft tissue as a slow growing, firm lump and may spread to the lymph nodes. If cancer formed in the arms, legs, or buttocks, a sentinel lymph node biopsy may be done to check for cancer in the lymph nodes.

- Alveolar soft part sarcoma. This is a rare tumor of the soft supporting tissue that connects and surrounds the organs and other tissues. It most commonly forms in the arms and legs but can occur in the tissues of the mouth, jaws, and face. It may grow slowly and often spreads to other parts of the body. Alveolar soft part sarcoma may have a better prognosis when the tumor is 5 centimeters or smaller or when the tumor is completely removed by surgery. The cells of this tumor usually have a certain genetic change called a translocation (part of the ASSPL gene switches places with part of the TFE3 gene). To diagnose alveolar soft part sarcoma, the tumor cells are checked for this genetic change.

- Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue. This is a slow-growing soft tissue tumor that begins in a tendon (tough, fibrous, cord-like tissue that connects muscle to bone or to another part of the body). Clear cell sarcoma most commonly occurs in deep tissue of the foot, heel, and ankle. It may spread to nearby lymph nodes. The cells of this tumor usually have a certain genetic change called a translocation (part of the EWSR1 gene switches places with part of the ATF1 or CREB1 gene). To diagnose clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue, the tumor cells are checked for this genetic change.

- Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. This type of soft tissue sarcoma may occur in children and adolescents. Over time, it tends to spread to other parts of the body, including the lymph nodes and lungs. The tumor may come back many years after treatment.

- Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma. See the PDQ summary on Ewing Sarcoma Treatment for information.

- Desmoplastic small round cell tumor. This tumor most often forms in the peritoneum in the abdomen, pelvis, and/or the peritoneum into the scrotum, but it may form in the kidney or other solid organs. Dozens of small tumors may occur in the peritoneum. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor may also spread to the lungs and other parts of the body. The cells of this tumor usually have a certain genetic change called a translocation (part of one chromosome switches places with part of another chromosome). To diagnose desmoplastic small round cell tumor, the tumor cells are checked for this genetic change.

- Extra-renal (extracranial) rhabdoid tumor. This fast-growing tumor forms in soft tissues such as the liver and bladder. It usually occurs in young children, including newborns, but it can occur in older children and adults. Rhabdoid tumors may be linked to a change in a tumor suppressor gene called SMARCB1. This type of gene makes a protein that helps control cell growth. Changes in the SMARCB1 gene may be inherited. Genetic counseling (a discussion with a trained professional about inherited diseases and a possible need for gene testing) may be needed.

- Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas). Benign PEComas may occur in children with an inherited condition called tuberous sclerosis. They occur in the stomach, intestines, lungs, and genitourinary organs. PEComas grow slowly and most are not likely to spread.

Undifferentiated/unclassified sarcoma. These tumors usually occur in the bones or the muscles that are attached to bones and that help the body move.

- Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma/malignant fibrous histiocytoma (high-grade). This type of soft tissue tumor may form in parts of the body where patients have received radiation therapy in the past, or as a second cancer in children with retinoblastoma. The tumor usually forms in the arms or legs and may spread to other parts of the body. (See the PDQ summary on Osteosarcoma and Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma of Bone Treatment for information about malignant fibrous histiocytoma of bone.)

Blood vessel tumors

Blood vessel tumors include the following types:

- Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas can occur in children, but are most common in adults between 30 and 50 years. They usually occur in the liver, lung, or in the bone. They may be fast growing or slow growing. In about a third of cases, the tumor spreads to other parts of the body very quickly. (See the PDQ summary on Childhood Vascular Tumors Treatment for more information.)

- Angiosarcoma of the soft tissue. Angiosarcoma of the soft tissue is a fast-growing tumor that forms in blood vessels or lymph vessels in any part of the body. Most angiosarcomas are in or near the skin. Those in deeper soft tissue can form in the liver, spleen, or lung. These tumors are very rare in children. Children sometimes have more than one tumor in the skin and/or liver. Rarely, infantile hemangioma may become angiosarcoma of the soft tissue. (See the PDQ summary on Childhood Vascular Tumors Treatment for more information.)

See the following PDQ summaries for information about types of soft tissue sarcoma not included in this summary:

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

The prognosis and treatment options depend on the following:

- The part of the body where the tumor first formed.

- The size and grade of the tumor.

- The type of soft tissue sarcoma.

- How deep the tumor is under the skin.

- Whether the tumor has spread to other places in the body and where it has spread.

- The amount of tumor remaining after surgery to remove it.

- Whether radiation therapy was used to treat the tumor.

- Whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has recurred (come back).

Stages of Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma

Key Points

- After childhood soft tissue sarcoma has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body.

- There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

- Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

- Sometimes childhood soft tissue sarcoma continues to grow or comes back after treatment.

After childhood soft tissue sarcoma has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the soft tissue or to other parts of the body is called staging. There is no standard staging system for childhood soft tissue sarcoma.

To plan treatment, it is important to know the type of soft tissue sarcoma, whether the tumor can be removed by surgery, and whether cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

The following procedures may be used to find out if cancer has spread:

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy: The removal of the sentinel lymph node during surgery. The sentinel lymph node is the first lymph node in a group of lymph nodes to receive lymphatic drainage from the primary tumor. It is the first lymph node the cancer is likely to spread to from the primary tumor. A radioactive substance and/or blue dye is injected near the tumor. The substance or dye flows through the lymph ducts to the lymph nodes. The first lymph node to receive the substance or dye is removed. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells. If cancer cells are not found, it may not be necessary to remove more lymph nodes. Sometimes, a sentinel lymph node is found in more than one group of nodes. This procedure is used for epithelioid and clear cell sarcoma.

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the chest, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

- PET scan: A PET scan is a procedure to find malignant tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Malignant tumor cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells do. This procedure is also called positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

- PET-CT scan: A procedure that combines the pictures from a PET scan and a computed tomography (CT) scan. The PET and CT scans are done at the same time on the same machine. The pictures from both scans are combined to make a more detailed picture than either test would make by itself.

There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

Cancer can spread through tissue, the lymph system, and the blood:

- Tissue. The cancer spreads from where it began by growing into nearby areas.

- Lymph system. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the lymph system. The cancer travels through the lymph vessels to other parts of the body.

- Blood. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the blood. The cancer travels through the blood vessels to other parts of the body.

Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

When cancer spreads to another part of the body, it is called metastasis. Cancer cells break away from where they began (the primary tumor) and travel through the lymph system or blood.

- Lymph system. The cancer gets into the lymph system, travels through the lymph vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

- Blood. The cancer gets into the blood, travels through the blood vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

The metastatic tumor is the same type of cancer as the primary tumor. For example, if soft tissue sarcoma spreads to the lung, the cancer cells in the lung are soft tissue sarcoma cells. The disease is metastatic soft tissue sarcoma, not lung cancer.

Sometimes childhood soft tissue sarcoma continues to grow or comes back after treatment.

Progressive childhood soft tissue sarcoma is cancer that continues to grow, spread, or get worse. Progressive disease may be a sign that the cancer has become refractory to treatment.

Recurrent childhood soft tissue sarcoma is cancer that has recurred (come back) after treatment. The cancer may come back in the same place or in other parts of the body.

Treatment Option Overview

Key Points

- There are different types of treatment for patients with childhood soft tissue sarcoma.

- Children with childhood soft tissue sarcoma should have their treatment planned by a team of health care providers who are experts in treating cancer in children.

- Seven types of standard treatment are used:

- New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

- Treatment for childhood soft tissue sarcoma may cause side effects.

- Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

- Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

- Follow-up tests may be needed.

There are different types of treatment for patients with childhood soft tissue sarcoma.

Different types of treatments are available for patients with childhood soft tissue sarcoma. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment.

Because cancer in children is rare, taking part in a clinical trial should be considered. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Children with childhood soft tissue sarcoma should have their treatment planned by a team of health care providers who are experts in treating cancer in children.

Treatment will be overseen by a pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with soft tissue sarcoma and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. These may include a pediatric surgeon with special training in the removal of soft tissue sarcomas. The following specialists may also be included:

Seven types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery

Surgery to completely remove the soft tissue sarcoma is done when possible. If the tumor is very large, radiation therapy or chemotherapy may be given first, to make the tumor smaller and decrease the amount of tissue that needs to be removed during surgery. This is called neoadjuvant (preoperative) therapy.

The following types of surgery may be used:

- Wide local excision: Removal of the tumor along with some normal tissue around it.

- Amputation: Surgery to remove all or part of the arm or leg with cancer.

- Lymphadenectomy: Removal of the lymph nodes with cancer.

- Mohs surgery: A surgical procedure used to treat cancer in the skin. Individual layers of cancer tissue are removed and checked under a microscope one at a time until all cancer tissue has been removed. This type of surgery is used to treat dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. It is also called Mohs micrographic surgery.

- Hepatectomy: Surgery to remove all or part of the liver.

A second surgery may be needed to:

- Remove any remaining cancer cells.

- Check the area around where the tumor was removed for cancer cells and then remove more tissue if needed.

If cancer is in the liver, a hepatectomy and liver transplant may be done (the liver is removed and replaced with a healthy one from a donor).

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, some patients may be given chemotherapy or radiation therapy after surgery to kill any cancer cells that are left. Treatment given after the surgery, to lower the risk that the cancer will come back, is called adjuvant therapy.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are two types of radiation therapy:

External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. Certain ways of giving radiation therapy can help keep radiation from damaging nearby healthy tissue. This type of radiation therapy may include the following:

- Stereotactic body radiation therapy: Stereotactic body radiation therapy is a type of external radiation therapy. Special equipment is used to place the patient in the same position for each radiation treatment. Once a day for several days, a radiation machine aims a larger than usual dose of radiation directly at the tumor. By having the patient in the same position for each treatment, there is less damage to nearby healthy tissue. This procedure is also called stereotactic external-beam radiation therapy and stereotaxic radiation therapy.

- Conformal radiation therapy: Conformal radiation therapy is a type of external radiation therapy that uses a computer to make a 3-dimensional (3-D) picture of the tumor and shapes the radiation beams to fit the tumor. This allows a high dose of radiation to reach the tumor and causes less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

- Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT): IMRT is a type of 3-dimensional (3-D) radiation therapy that uses a computer to make pictures of the size and shape of the tumor. Thin beams of radiation of different intensities (strengths) are aimed at the tumor from many angles. This type of external radiation therapy causes less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

- Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer.

Whether the radiation therapy is given before or after surgery to remove the cancer depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated, if any cancer cells remain after surgery, and the expected side effects of treatment. External and internal radiation therapy are used to treat childhood soft tissue sarcoma.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy). When chemotherapy is placed directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, an organ, or a body cavity such as the abdomen, the drugs mainly affect cancer cells in those areas (regional chemotherapy). Combination chemotherapy is the use of more than one anticancer drug.

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a type of treatment used during surgery that is being studied for desmoplastic small round cell tumor. After the surgeon has removed as much tumor tissue as possible, warmed chemotherapy is sent directly into the peritoneal cavity.

The way the chemotherapy is given depends on the type of soft tissue sarcoma being treated. Most types of soft tissue sarcoma do not respond to treatment with chemotherapy.

See Drugs Approved for Soft Tissue Sarcoma for more information.

Observation

Observation is closely monitoring a patient’s condition without giving any treatment until signs or symptoms appear or change. Observation may be done when:

- Complete removal of the tumor is not possible.

- No other treatments are available.

- The tumor is not likely to damage any vital organs.

Observation may be used to treat desmoid-type fibromatosis, infantile fibrosarcoma, PEComa, or epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of treatment that uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells. Targeted therapies usually cause less harm to normal cells than chemotherapy or radiation therapy do.

Kinase inhibitors block an enzyme called kinase (a type of protein). There are different types of kinases in the body that have different actions.

- ALK inhibitors may stop the cancer from growing and spreading. Crizotinib may be used to treat inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, infantile fibrosarcoma, and clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue.

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) block signals needed for tumors to grow. Imatinib is used to treat dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Pazopanib may be used to treat desmoid-type fibromatosis, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and some types of recurrent and progressive soft tissue sarcoma. Sorafenib may be used to treat desmoid-type fibromatosis and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Sunitinib may be used to treat alveolar soft part sarcoma. Larotrectinib is used to treat infantile fibrosarcoma. Ceritinib is used to treat inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Axitinib may be used to treat some types of progressive soft tissue sarcoma, including alveolar soft part sarcoma.

- mTOR inhibitors are a type of targeted therapy that stops the protein that helps cells divide and survive. mTOR inhibitors are being used to treat recurrent desmoplastic small round cell tumors, PEComas, and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and are being studied to treat malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Sirolimus and temsirolimus are types of mTOR inhibitor therapy.

New types of tyrosine kinase inhibitors are being studied such as:

- Entrectinib and selitrectinib for infantile fibrosarcoma.

- Trametinib for epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

Other types of targeted therapy are being studied in clinical trials, including the following:

- Angiogenesis inhibitors are a type of targeted therapy that prevent the growth of new blood vessels needed for tumors to grow. Angiogenesis inhibitors, such as cediranib, sunitinib, and thalidomide are being studied to treat alveolar soft part sarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Bevacizumab is being used to treat angiosarcoma.

- Histone methyltransferase (HMT) inhibitors are targeted therapy drugs that work inside cancer cells and block signals needed for tumors to grow. HMT inhibitors, such as tazemetostat, are being studied for the treatment of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, epithelioid sarcoma, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, and extrarenal (extracranial) rhabdoid tumor.

- Heat-shock protein inhibitors block certain proteins that protect tumor cells and help them grow. Ganetespib is a heat shock protein inhibitor being studied in combination with the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors that cannot be removed by surgery.

- NOTCH pathway inhibitors are a type of targeted therapy that works inside the cancer cells and blocks signals needed for tumors to grow. NOTCH pathway inhibitors are being studied for the treatment of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Gamma-secretase inhibitors, such as nirogacestat, are a type of NOTCH pathway inhibitors.

See Drugs Approved for Soft Tissue Sarcoma for more information.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defenses against cancer. This cancer treatment is a type of biologic therapy.

Interferon and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy are types of immunotherapy.

- Interferon interferes with the division of tumor cells and can slow tumor growth. It is used to treat epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

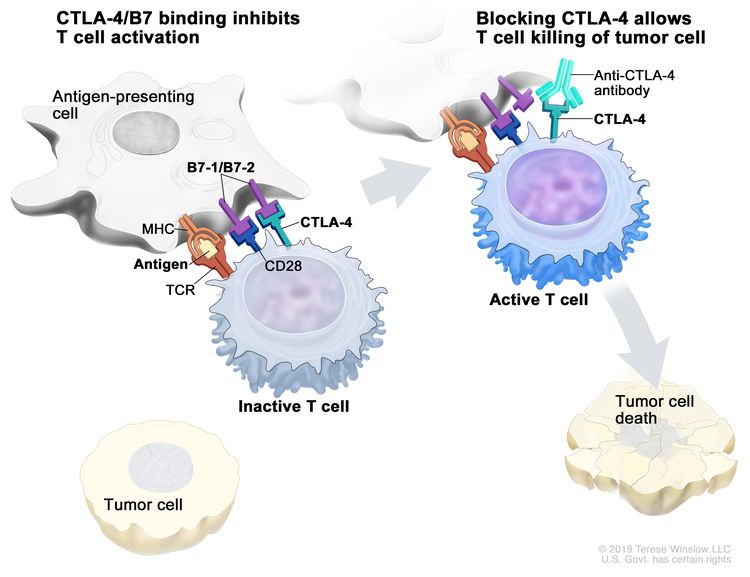

Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: Some types of immune cells, such as T cells, and some cancer cells have certain proteins, called checkpoint proteins, on their surface that keep immune responses in check. When cancer cells have large amounts of these proteins, they will not be attacked and killed by T cells. Immune checkpoint inhibitors block these proteins and the ability of T cells to kill cancer cells is increased.

There are two types of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy:

CTLA-4 inhibitor therapy: CTLA-4 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body’s immune responses in check. When CTLA-4 attaches to another protein called B7 on a cancer cell, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. CTLA-4 inhibitors attach to CTLA-4 and allow the T cells to kill cancer cells. Ipilimumab is a type of CTLA-4 inhibitor that is being studied to treat angiosarcoma.

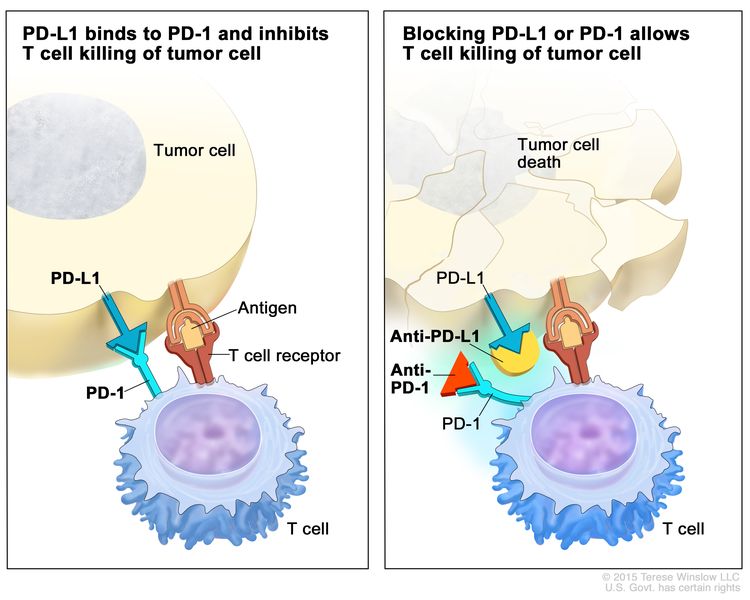

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint proteins, such as B7-1/B7-2 on antigen-presenting cells (APC) and CTLA-4 on T cells, help keep the body’s immune responses in check. When the T-cell receptor (TCR) binds to antigen and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins on the APC and CD28 binds to B7-1/B7-2 on the APC, the T cell can be activated. However, the binding of B7-1/B7-2 to CTLA-4 keeps the T cells in the inactive state so they are not able to kill tumor cells in the body (left panel). Blocking the binding of B7-1/B7-2 to CTLA-4 with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) allows the T cells to be active and to kill tumor cells (right panel). PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitor therapy: PD-1 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body’s immune responses in check. PD-L1 is a protein found on some types of cancer cells. When PD-1 attaches to PD-L1, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors keep PD-1 and PD-L1 proteins from attaching to each other. This allows the T cells to kill cancer cells. Pembrolizumab is a type of PD-1 inhibitor that is used to treat progressive and recurrent soft tissue sarcoma. Nivolumab is a type of PD-1 inhibitor that is being studied to treat angiosarcoma. Atezolizumab is a type of PD-L1 inhibitor that is being studied to treat alveolar soft part sarcoma.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint proteins, such as PD-L1 on tumor cells and PD-1 on T cells, help keep immune responses in check. The binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 keeps T cells from killing tumor cells in the body (left panel). Blocking the binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (anti-PD-L1 or anti-PD-1) allows the T cells to kill tumor cells (right panel).

Other Drug Therapy

Steroid therapy has antitumor effects in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors.

Hormone therapy is a cancer treatment that removes hormones or blocks their action and stops cancer cells from growing. Hormones are substances made by glands in the body and circulated in the bloodstream. Some hormones can cause certain cancers to grow. If tests show that the cancer cells have places where hormones can attach (receptors), drugs, surgery, or radiation therapy is used to reduce the production of hormones or block them from working. Antiestrogens (drugs that block estrogen), such as tamoxifen, may be used to treat desmoid-type fibromatosis. Prasterone is being studied for the treatment of synovial sarcoma.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are drugs (such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen) that are commonly used to decrease fever, swelling, pain, and redness. In the treatment of desmoid-type fibromatosis, an NSAID called sulindac may be used to help block the growth of cancer cells.

New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

This summary section describes treatments that are being studied in clinical trials. It may not mention every new treatment being studied. Information about clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Gene therapy

Gene therapy is being studied for childhood synovial sarcoma that has recurred, spread, or cannot be removed by surgery. Some of the patient's T cells (a type of white blood cell) are removed and the genes in the cells are changed in a laboratory (genetically engineered) so that they will attack specific cancer cells. They are then given back to the patient by infusion.

Treatment for childhood soft tissue sarcoma may cause side effects.

For information about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, see our Side Effects page.

Side effects from cancer treatment that begin after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include:

- Physical problems.

- Changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory.

- Second cancers (new types of cancer).

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the effects cancer treatment can have on your child. (See the PDQ summary on Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer for more information.)

Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today's standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

Some clinical trials only include patients who have not yet received treatment. Other trials test treatments for patients whose cancer has not gotten better. There are also clinical trials that test new ways to stop cancer from recurring (coming back) or reduce the side effects of cancer treatment.

Clinical trials are taking place in many parts of the country. Information about clinical trials supported by NCI can be found on NCI’s clinical trials search webpage. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Follow-up tests may be needed.

Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer or to find out the stage of the cancer may be repeated. Some tests will be repeated in order to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back). These tests are sometimes called follow-up tests or check-ups.

Treatment of Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Fat Tissue Tumors

Liposarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed liposarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery to completely remove the tumor. If the cancer is not completely removed, a second surgery may be done.

- Chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery.

- Radiation therapy before or after surgery.

Bone and Cartilage Tumors

Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery to completely remove the tumor. Radiation therapy may be given before and/or after surgery.

- Chemotherapy followed by surgery. Chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy is given after surgery.

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed extraskeletal osteosarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery to completely remove the tumor, followed by chemotherapy.

See the PDQ summary on Osteosarcoma and Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma of Bone Treatment for more information about treatment of osteosarcoma.

Fibrous (Connective) Tissue Tumors

Desmoid-type fibromatosis

Treatment of newly diagnosed desmoid-type fibromatosis may include the following:

- Observation, for asymptomatic tumors, tumors that are not likely to damage any vital organs, and tumors that are not completely removed by surgery.

- Chemotherapy for tumors that are not completely removed by surgery or that have recurred.

- Targeted therapy (sorafenib or pazopanib).

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy.

- Antiestrogen drug therapy.

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy.

- A clinical trial of targeted therapy with a NOTCH pathway inhibitor.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Treatment of newly diagnosed dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may include the following:

- Surgery to completely remove the tumor when possible. This may include Mohs surgery.

- Radiation therapy before or after surgery.

- Radiation therapy and targeted therapy (imatinib) if the tumor cannot be removed or has come back.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

Treatment of newly diagnosed inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor may include the following:

- Surgery to completely remove the tumor when possible.

- Chemotherapy.

- Steroid therapy.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy.

- Targeted therapy (crizotinib and ceritinib).

Fibrosarcoma

Infantile fibrosarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed infantile fibrosarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor when possible, followed by observation.

- Surgery

- Chemotherapy

- Targeted therapy (crizotinib and larotrectinib).

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient's tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

- A clinical trial of targeted therapy (larotrectinib, entrectinib, or selitrectinib).

Adult fibrosarcoma

Treatment of adult newly diagnosed fibrosarcoma may include the following:

Myxofibrosarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed myxofibrosarcoma may include the following:

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma may include the following:

Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma may include the following:

Skeletal Muscle Tumors

Rhabdomyosarcoma

See the PDQ summary on Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment.

Smooth Muscle Tumors

Leiomyosarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed leiomyosarcoma may include the following:

So-called Fibrohistiocytic Tumors

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor

Treatment of newly diagnosed plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor may include the following:

Nerve Sheath Tumors

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

Treatment of newly diagnosed malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor may include the following:

- Surgery to completely remove the tumor when possible.

- Radiation therapy before or after surgery.

- Chemotherapy, for tumors that cannot be removed by surgery.

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient's tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

It is not clear whether giving radiation therapy or chemotherapy after surgery improves the tumor's response to treatment.

Malignant triton tumor

Newly diagnosed malignant triton tumors may be treated the same as rhabdomyosarcomas and include surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy. It is not clear whether giving radiation therapy or chemotherapy improve the tumor's response to treatment.

Ectomesenchymoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed ectomesenchymoma may include the following:

Pericytic (Perivascular) Tumors

Infantile hemangiopericytoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed infantile hemangiopericytoma may include the following:

Infantile myofibromatosis

Treatment of newly diagnosed infantile myofibromatosis may include the following:

Tumors of Unknown Cell Origin (the place where the tumor first formed is not known)

Synovial sarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed synovial sarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery. Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may be given before or after surgery.

- Chemotherapy

- Stereotactic radiation therapy for tumors that have spread to the lung.

Epithelioid sarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed epithelioid sarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor when possible.

- Chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy before or after surgery.

Alveolar soft part sarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed alveolar soft part sarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery to completely remove the tumor when possible.

- Radiation therapy before or after surgery, if the tumor cannot be completely removed by surgery.

- Targeted therapy (sunitinib).

- A clinical trial of immunotherapy (atezolizumab).

Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue

Treatment of newly diagnosed clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor when possible.

- Radiation therapy before or after surgery.

- Targeted therapy (crizotinib).

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor when possible.

- Radiation therapy.

Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma

See the PDQ summary on Ewing Sarcoma Treatment.

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

There is no standard treatment for newly diagnosed desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Treatment may include the following:

- Surgery to completely remove the tumor when possible.

- Surgery

- Chemotherapy followed by surgery.

- Radiation therapy.

- Chemotherapy

Extra-renal (extracranial) rhabdoid tumor

Treatment of newly diagnosed extra-renal (extracranial) rhabdoid tumor may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor when possible.

- Chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy.

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient's tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas)

Treatment of newly diagnosed perivascular epithelioid cell tumors may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor.

- Observation followed by surgery.

- Targeted therapy (sirolimus), for tumors that have certain gene changes and cannot be removed by surgery.

Undifferentiated/Unclassified Sarcoma

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma/malignant fibrous histiocytoma (high-grade)

There is no standard treatment for these tumors.

See the PDQ summary on Osteosarcoma Treatment for information about the treatment of malignant fibrous histiocytoma of bone.

Blood Vessel Tumors

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

Treatment of newly diagnosed epithelioid hemangioendothelioma may include the following:

- Observation.

- Surgery to remove the tumor when possible.

- Immunotherapy (interferon) and targeted therapy (thalidomide, sorafenib, pazopanib, sirolimus) for tumors that are likely to spread.

- Chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy.

- Total hepatectomy and liver transplant when the tumor is in the liver.

- A clinical trial of targeted therapy (trametinib).

Angiosarcoma of soft tissue

Treatment of newly diagnosed angiosarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery to completely remove the tumor.

- A combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy for angiosarcomas that have spread.

- Targeted therapy (bevacizumab) and chemotherapy for angiosarcomas that began as infantile hemangiomas.

- A clinical trial of immunotherapy (nivolumab and ipilimumab).

Metastatic Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma

Treatment of childhood soft tissue sarcoma that has spread to other parts of the body at diagnosis may include the following:

- Chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Surgery may be done to remove tumors that have spread to the lung.

- Stereotactic body radiation therapy for tumors that have spread to the lung.

For treatment of specific tumor types, see the Treatment Options for Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma section.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

Treatment of Progressive or Recurrent Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of progressive or recurrent childhood soft tissue sarcoma may include the following:

- Surgery to remove cancer that has come back where it first formed or that has spread to the lung.

- Surgery

- Surgery

- Surgery

- Chemotherapy

- Targeted therapy (pazopanib or axitinib).

- Immunotherapy (pembrolizumab).

- Stereotactic body radiation therapy for cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, especially the lung.

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient's tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

To Learn More About Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma

For more information from the National Cancer Institute about childhood soft tissue sarcoma, see the following:

For more childhood cancer information and other general cancer resources, see the following:

- About Cancer

- Childhood Cancers

- CureSearch for Children's Cancer

- Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer

- Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer

- Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents

- Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- Staging

- Coping with Cancer

- Questions to Ask Your Doctor about Cancer

- For Survivors and Caregivers

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government’s center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood soft tissue sarcoma. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma/patient/child-soft-tissue-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389342]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s E-mail Us.

Updated:

This content is provided by the National Cancer Institute (www.cancer.gov)

Source URL: https://www.cancer.gov/node/5296/syndication

Source Agency: National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Captured Date: 2013-09-14 09:02:45.0